Program

Program overview and lecture material.

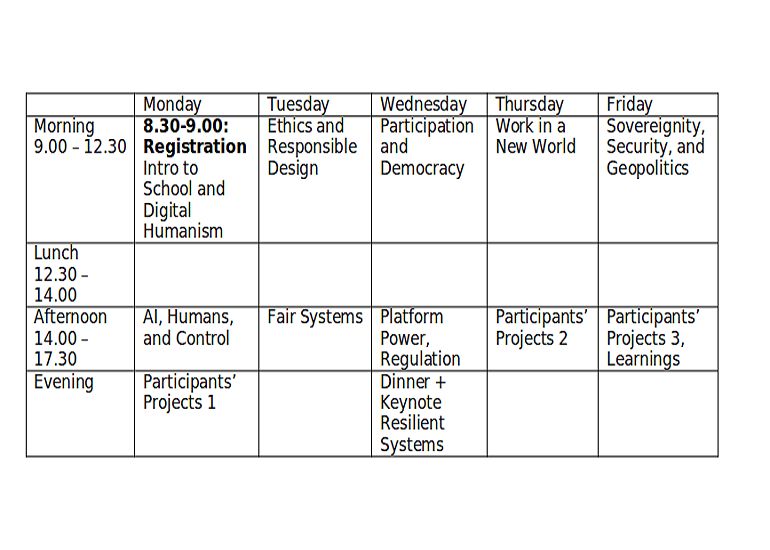

Program Overview (Times in CEST)

Detailed Program

Monday

8:30-9:00

Registration

Morning (9:00-12:30)

Welcome and Introduction H. Werthner: Welcome and Overview of the Program

H. Werthner: Digital Humanism – an Introduction

slidesI will briefly reflect on the history of computer science, its success and potentials as well as negative impacts, and then discuss the need for an interdisciplinary response to these shortcomings. Such an answer is the Digital Humanism, which looks at this interplay of technology and humankind, it analyzes, and, most importantly, tries to influence the complex interplay of technology and humankind, for a better society and life. I will discuss this approach and its core principles as they are expressed in the Vienna Manifesto on Digital Humanism, I will show what was achieved since its first workshop in 2019, and which challenges lie ahead.

G. Metakides: No Time for Complacency

slidesH. Akkermans: Societal Responsibilities of the Digital Scientist and Professional: Techno-sociality, Critical Science, Reflective Action

slidesDigital Humanism entails a moral position on human flourishing also in the digital domain. It is more than that: morality has a rational basis (“reason”). In this talk I argue: (i) digital technology is inherently value-laden; (ii) evolutionary paths of digital technology are not pre-determined, but open for (also democratic) influences; (iii) digital scientists and professionals have (whether they want it or not) a role in this, and hence they cannot stick to some “neutral” technical approach that ignores the wider social and societal consequences of their work.

Afternoon (14:00-17:30)

AI, Humans, and Control

This segment of the summer school will examine the extent to which humans are in control of the trajectory of technology development. Where such control is limited, accountability becomes more challenging. Specifically, we will focus on artificial intelligence and identify the conditions under which an AI itself becomes accountable for its actions.

For more than 50 years, humans have been using model- and data-based support systems in decision making with the hope that system supported decisions are not only better, more objective and fairer (i.e., more efficient and less biased). With data-based Artificial Intelligence systems, this hope is revived. However, the delegation of tasks and decision-making to automated decision systems is accompanied by the assignment and attribution of (social) agency to these systems. We will discuss how role perceptions, expectations and attribution of agency may change for human actors and cause diffusion of accountability, over-trust in automated systems and reduced autonomy and self-efficacy of human actors. We will examine how automated decision systems impact the autonomy of humans and what requirements are to be placed on automated decision systems in order to protect individuals and society.

Assuring that AI systems and services operate in accordance with agreed norms and principles is essential to foster trust and facilitate their adoption. Ethical assurance requires a global ecosystem, where organisations not only commit to upholding human values, dignity, and well-being, but are also able to demonstrate this when required by the specific context in which they operate. The talk will focus on possible instruments and governance mechanisms of such a Human Centered AI Ecosystem.

Evening (18:30-21:00)

Participants’ Projects 1

C. Ghezzi, J. Kramer, B. Nuseibeh

slidesThe project sessions will engage participants in an exploration of how the values of digital humanism can inform and guide the conception of socio-technical systems. The focus is on understanding (probably conflicting) goals that such systems should achieve, drawing on multiple perspectives to consider a wider spectrum of human and technical issues, and embracing an interdisciplinary approach to account for political, economic, environmental, and social values and concerns. Goals can be used to justify and describe the requirements that a system is expected to achieve, avoid, maintain or satisfy to some acceptable degree. The main aim of the sessions is to encourage students to engage with the challenges of eliciting, articulating, and organising various digital humanism issues that are presented in the school, as system goals. Participants might also elaborate on the features that systems should support to achieve their goals, and how it would be possible to ascertain whether an existing system is compliant with what was initially expected.

* Why do we engage you in a project?

* How is the project related to the other topics ?

* How is the project activity structured?

* Some tools to organize your work.

* Interdisciplinary group formation.

Tuesday

Morning (9:00-12:30)

Ethics and Responsible Design

Climate warming and the threat of nuclear conflicts raise global ethical issues concerning the welfare and fundamental rights of all human beings at once. What are the environmental duties of AI research and industrial communities on account of the growing AI carbon footprint? What risks for worldwide peace and stability arise from the envisaged incorporation of AI technologies into nuclear command, control and communication? These emerging issues have a profound impact on the AI ethics agenda, until recently focused on ethical issues lacking this global dimension.

The traditional framework of ‘passive’ responsibility in the ethics of technology (where the discussion on responsibility emerges only when something undesirable occurs) is not enough to deal with sophisticated digital technologies, such as AI. Here an active approach to the concept or responsibility is required. These technologies should be designed not only to possibly avoid negative consequences, but also to promote positive outcomes. The ‘moralization’ of technologies is thus the deliberate development of technologies in order to shape moral action and decision-making. In this lecture I will present this idea by means of some examples used to support the class discussion. The goal is to evidence the promises of this approach, but also its challenges that deal, in particular, with human autonomy and the opacity of some design choices.

Technology is no longer just about technology – now it is about living. So, how do we have ethical technology that creates a better society and life? Technology must become truly “human-centered,” not just “human-aware” or “human-adjacent”. Diverse users and advocacy groups must become equal partners in initial co-design and in continual assessment and management. But we cannot get there without radically transforming how we think about, create and use technologies. We will explore new models for digital humanism and discuss effective tools and techniques for designing, building, and maintaining systems that are continually ethical, responsible, and human-centered.

Afternoon (14:00-17:30)

Fair Systems

Many Web ecosystems such as Facebook, Google, Amazon, Uber, and many more are not considered as fair. This is amongst other demonstrated by the European Commission, who fines the dominant parties of these ecosystems regularly. We explain, in a model-based way why such ecosystems are unfair, and how the model can tell this. We also give some guidelines how to design fair ecosystems and the required decentralized information technology to accomplish these. We also give some examples of ecosystems that are from a structural point fairer than the well-known platform-oriented systems.

Despite the huge impact of digital technologies on the lives of all people on the planet, many, especially in the Global South, are not included in the debate about the future of the digital society. Governance of the digital society is still concentrated in the Global North. We refer to this problem as “digital coloniality”. To design fair (eco-)systems in the global digital society, involvement of communities from all regions of the world is necessary. In this lecture we discuss cases of collaborative, community-oriented, transdisciplinary technology design for a more inclusive digital society.

S. Mendis: Copyright, Democratic Discourse and Platform Governance: The Need for a Paradigm Shift

slides videoOnline social media platforms constitute a core component of the contemporary digital public sphere. Thus, although typically owned and administered by private-sector corporate entities, their governance should be aimed at achieving the public interest objective of promoting robust democratic discourse within these digital spaces. This lecture argues that the existing EU legal framework on online copyright enforcement is rooted in a narrow utilitarian-based normative framework that renders it unfit for achieving a fair balance between protecting the economic interests of copyright owners and the interests of users to engage in legitimate discourse. It espouses a re-imagining of the existing framework on online copyright enforcement based on the normative framework provided by the social planning theory (communicational theory) of copyright which envisions copyright law as an instrument for promoting the discursive foundations of democratic culture and civic association.

Wednesday

Morning (9:00-12:30)

Participation and Democracy

Direct, participatory democracy was (in spite of it being limited to property owning free males) a revolutionary idea born by and for the “demos” of the 5th century Athenian polis. Contrary to much popular belief, democracy did not spread widely nor did it last long. After a brief flickering in early Roman times, its flame remained effectively extinguished for centuries, to reappear with the “nation” replacing the demos and representation replacing direct participation in the 19th century. Following a brief period of “democratic euphoria” in the start of the decade of the 90’s, a quick survey of measurements/indices today shows a representative democracy in crisis and in retreat globally. Current analyses attribute this to an internal degeneration caused by several factors and propose various “upgrades” of the “technology of democracy” employing digital technologies towards a sort of Democracy 2.0 as a counterweight to other effects of digital technologies that are perceived as negative.

G. Zarkadakis: Using AI and Cryptoeconomics to Facilitate Citizen Deliberations at Scale

slides videoI will describe the development of an innovative software platform that implements a model of participatory democracy for the web. The platform aims to provide a valuable tool to mutli-stakeholder organizations, such as cities, associations, trade unions, cooperatives, etc., so that they may engage meaningfully with their members and arrive at collective decisions on potentially polarizing.

A. Stanger: Are Cryptocurrencies and Decentralized Finance Democratic?

videoWhile the best and brightest in the US are now headed to Web3 startups, public opinion is divided on Web3 technologies. Crypto’s advocates laud its reliance on technology rather than governments to enforce contracts, thereby cutting out the middlemen, so its principles seem participatory and democratic in theory. In practice, however, plutocratic predatory behavior has carried the day and is anything but democratic.

G. Metakides and all: Conclusions

videoFollowing the presentation of concrete “democracy-positive” and “democracy-negative” uses and applications of digital technologies, a brief survey of all other known related applications (both existing and proposed) will be provided together a perusal of underlying socioeconomic and geopolitical factors eroding trust in politicians, politics and democracy itself by citizens in general and young ones in particular. This will set the scene for an attempt at conclusions about the future of citizen participation in and support for representative democracy in the digital era and related discussion.

Afternoon (14:00-17:30)

Platform Power, Regulation

In this lecture I will cover the following three topics, each with examples and empirical evidence:

- Online platforms as markets,

- Online platforms as organisation,

- Online platforms and the issue of data protection and algorithmic transparency.

The focus of this lecture is on platform regulation, on mergers and antitrust. I will start by looking at the various theories of possible harm from platform mergers, and when platforms be required to notify competition authorities of planned mergers. I will also touch the difference between horizontal and vertical mergers. A further question is what are ways to increase market data visibility.

Evening (19:00)

at the Vienna City Library, Rathaus, Entrance Lichtenfelsgasse 2 – Stiege 6, 1. Stock / staircase #6, 1st floor

V. Kaup-Hasler (Executive City Councillor for Cultural Affairs and Science): Welcome Address

M. Vardi (Keynote): Lessons from Texas, COVID-19 and the 737 Max: Efficiency vs Resilience

slides videoIn both computer science and economics, efficiency is a cherished property. The field of algorithms is almost solely focused on their efficiency. The goal of AI research is to increase efficiency by reducing human labor. In economics, the main advantage of the free market is that it promises “economic efficiency”. A major lesson from many recent disasters is that both fields have over-emphasized efficiency and under-emphasized resilience. I argue that resilience is a more important property than efficiency and discuss how the two fields can broaden their focus to make resilience a primary consideration.

Thursday

Morning (9:00-12:30)

Ethics and Responsible Design

Work and the production of goods and services have always been shaped by available technologies. This lecture reviews how technological change have influenced the world of work in historical perspective. Policy challenges and opportunities for jobs, work and incomes that are brought about by digital technologies are highlighted and discussed. Some aspects of the research agenda of the International Labour organization (ILO) in this area will be presented to the course participants and be debated.

This lecture explores the role of digital platform labor in the development of today’s artificial intelligence. The first part describes how platforms allocate underpaid or unpaid tasks to users via on-demand labor, microwork and socially networked labor. In order to coordinate users’ contributions, platforms “taskify” labor processes. In the second part, we will focus on the companies that specialize in recruiting and managing data task providers. They produce three types of contributions: “AI preparation”, “AI verification”, and “AI impersonation”. Digital labor is a structural component of automation and an essential part of contemporary AI production processes – not an ephemeral form of support that may vanish once the technology reaches maturity stage. In the third part, we analyze the policy implications of a future in which automation does not replace human workforce but drives its marginalization and precarization.

Afternoon (14:00-17:30)

Fair Systems

Extra session by Titus Leber

videoC. Ghezzi, J. Kramer, B. Nuseibeh

Session 2: Participants work in their groups.

Friday

Morning (9:00-12:30)

Sovereignity, Security, Geopolitics

The overall structure of IT services has substantial influence on the possible misuse of data, where the big picture contributes to transparency and sets out the baseline for data protection and digital sovereignty. Today mobile devices play a key role. This brings a set of players – the service provider, the mobile communications provider and the manufacturer of the mobile system – on the plan, where users are not aware of possible data flows and where Cloud plays a central role. It is key to understand the impact of Cloud not only on privacy but also on sovereignty especially as Cloud is often one way. We might use public services like a few times a month and private services several times a day – openness is the only way to harvest synergies with the private sector. Public administration is challenged to use Social Media as well as new technologies like Blockchain and AI which will change public administration. How to safeguard national interests and sovereignty? These are some of the challenges for an „eGov for all“ approach where in many cases public services exhibit clear differences compared with the private sector.

Digital sovereignty and strategic autonomy have become Chefsache. I start with a short intro into sovereignty and international relations. Then we will go into how the digital age changes perceptions of sovereignty. This will address: threats and sovereignty gap; sovereignty and values or norms in the digital age; safeguarding autonomy in digital economy, society and democracy; security of the state and securitization; governance, nationally and internationally, public and private. We then focus on strategies to contribute with ‘digital’ to sovereignty (i.e. digital sovereignty or digital strategic autonomy), with special attention to the global level. A case study of ‘sovereignty in the digital age and the EU’ illustrates the theoretical frameworks and analysis. I conclude with the challenge to the studen,ts: what could be the shape of digital humanism-based sovereignty in the digital age?

Afternoon (14:00-17:30)

Participants’ Projects 3

C. Ghezzi, J. Kramer, B. Nuseibeh

videoSession 3: Participants present their results in a plenary session and these results are discussed

Learnings of the Summer School

Final discussion – what we learned